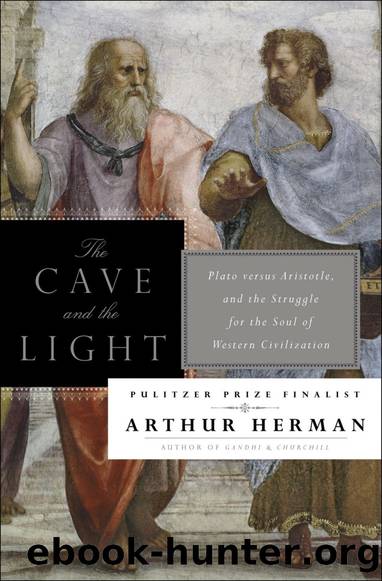

The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization by Arthur Herman

Author:Arthur Herman [Herman, Arthur]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780553907834

Google: 4VH1Jcj6nq4C

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 13534181

Publisher: Random House Publishing Group

Published: 2013-10-22T05:00:00+00:00

Not many tourists go to the northeast Italian town of Padua today, except perhaps to see Giottoâs famous frescoes in the Arena Chapel. However, for more than one hundred years after Giotto put away his brushes and closed his paint pots, Renaissance Padua was Europeâs leading school of natural philosophy, or what today we call science.

The fiercely empirical spirit of Roger Baconâs Oxford and Ockhamist Paris had found a new home in the University of Padua. Like Bacon, Paduaâs teachers stressed the original principle of Aristotleâs philosophy of nature: that knowledge is a process of discovery using the power of our senses. As one of Paduaâs most celebrated teachers put it, âAll [knowledge] progresses from the known to the unknown.â5 The Paduan Aristotelians taught students that the scientist should never be afraid to venture into unfamiliar territory. He may not only discover something new, he can add new support for tried-and-true scientific principlesâwhich, as far as Padua was concerned, meant Aristotleâs principles.

All this sounds very modern.6 So we arenât surprised to learn that one of Paduaâs distinguished alumni was Nicolaus Copernicus or that professors there were experimenting with rolling balls on inclined planes and swinging pendulums on horizontal crossbars. Nor are we amazed that the star of Paduaâs school of medicine was Andreas Vasalius, who led the first classes on human dissection since the ancient Greeks; or that in 1592, the university decided to hire a twenty-eight-year-old mathematician from Pisa named Galileo Galilei.7

Padua sounds like the perfect environment for a sharp, inquiring mind like Galileoâs. But he was deeply unhappy there.8 Why?

There are rows and rows of books on Galileo. There is even a book about Galileoâs daughter. No one has yet written a bestseller about Galileoâs father, but Vincenzo Galilei may hold the real key to understanding his more famous son.

Galilei worked as a court musician for the Medici in Florence in the 1560s and 1570s and published treatises on the theory of music. Glancing through the pages of his works, we see diagrams that remind us forcibly of diagrams of planetary movement in his sonâs works.9 The reason is that Vincenzo Galilei was a mathematician as well as a musicologist. His goal was to return musical theory to its Pythagorean roots. The father, like the son, understood the power of number not as a way to count or measure, as Aristotelians did, but rather as Number, reasonâs window into the hidden order of nature.

Vincenzo must have demonstrated this to his son more than once, by picking up his lute and strumming a single note. Then he would put his sonâs finger in the exact midpoint of the string and strike it again. The note would rise exactly an octave. Vincenzo would move his finger again, and the note rose proportionately to the next octave, and so on.*

Pythagoras was the first to demonstrate that mathematical proportion was the essence of musical harmony. He also passed to his disciple Plato the notion that proportion was endowed with creative power. By cutting the string in half, we create two octaves where there was only one.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8896)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8311)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7256)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7064)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6758)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6557)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5712)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5683)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5459)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5153)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4399)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4278)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4244)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4218)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4206)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4176)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4098)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3962)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3926)